1.Introducing the 2018 Deltaworkers residents, from left to right: Saskia Janssen, Alma Matthijssen, George Korsmit, Io Cooman, Camp Abundance, 8 maart 2018.

In 2015 we visited New Orleans for the first time. We stayed only a week and we fell in love with the city and her southern vibe. But not only that. We were also shocked by the segregation, the inequality and the poverty that we witnessed here more than anywhere else in the VS. And we were impressed by the people and the many ways of self organization and civil initiatives on many levels. Our intention was definitely to come back one day.

In 2005 we founded the Rainbow Soulclub in the Blaka Watra shelter in Amsterdam, a shelter for homeless people and long term drug addicts, mainly from Surinamese origin.

The Rainbow Soulclub is a collaborative project: artists, art students and clients from the shelter meet each other already 12 years every Friday in the shelter. During those years a whole variety of activities came about. Not only a large art production and many exhibitions, but also field trips, workshops, performances, demonstrations, various publications and a travel to Ghana and Surinam were organized. It didn’t start off with a specific agenda, there was no plan from the beginning, and no idea about the outcome. It started almost as if it were a blind date between two different groups of people. Organically it became a collective of individuals who are interested in each other and undertake activities they wouldn’t do without each other.

For our residency at Deltaworkers we are interested in New Orleans’ citizens’ initiatives, a.o. grass roots movements, civil right activism, alternative ways of healing, small scale methods of raising awareness. How to deal with a racist past and the outcome of that past? How to change the present situation? What role can art play, if at all? How to deal with a government you didn’t vote for? Just a few of the many topical questions we ask ourselves here in New Orleans.

Deltaworkers is a research residency. That means that there is no concrete art production expected and there is no studio space or whatsoever to produce works. At first that feels slightly uncomfortable, as we are always in the mood to make new works and always wish to come home with ‘results’ of a travel, a residency. Producing (and exhibiting) works seems the natural satisfying mode for an artist in general and we are no exception here. But there is definitely something to learn about this attitude, especially in a place like New Orleans. Even though the Rainbow Soulclub changed our mentality already and shaped our awareness during the years; it made clear to us that ‘the path to the goal’ is the goal in itself.

Already after the first week it doesn’t feel right to arrive here as an outsider and to be quick with gathering ‘results’, hunting for inspiration or trying to find collaboration partners. New Orleans is a magnet for photographers, musicians, filmmakers and what we often hear is: ‘they all come here for inspiration, they earn money by publishing photo books, films, even HBO tv series whatsoever, but what’s in it for us?’ Art is not everywhere high on the agenda, if at all and that is understandable. To be a (white) artist is a privilege and here we feel more white and privileged then ever before.

We decide first to try to understand more of the current New Orleans; the city, the streets, the people, the complex history of the Southern States, Katrina. Every day we walk and bike the streets for hours, meeting people, listening to stories, opinions, experiences, with no intention to transform this all into art works, just listening, being open, receptive, non judgemental, no plans. It appears to us that the majority of visitors stay in the French Quarter around Bourbon street and have no desire to visit the various other neighbourhoods. Partly because they come especially for the booze & the bars and partly because they believe it is too dangerous in many places. Even travel guides advise to avoid a historically and culturally important neighbourhood like Tremé. (Later, a Tremé local will tell us that this is a strategy of the tour guides, in order to keep the tourist money in the French Quarter.)

March 2018

The Backstreet Cultural Museum in Tremé is one of the first places we visit and we will come back here several times. It is a private museum of the Mardi Grass Indian culture, founded in 1999 by Sylvester Francis. Originally it was based in a two-car garage, later it moved to a former funeral home. It is still run by mr. Francis and his family who give personal tours through the rooms.. All displays are self made and the costumes at display are self made by the Black Indians and donated by them. The museum is financed by the entrance fees and by donations. We learn about mr. Ashton Ramsey, a local historian, artist and activist who makes his own activist suits already for years. We will meet him later in a parade where he invites us to visit his studio in the Bywater.

The Backstreet Cultural Museum in the Henriette DeLille st.

The Backstreet Cultural Museum in the Henriette DeLille st.

The Backstreet Cultural Museum in the Henriette DeLille st.

In order to ‘understand’ New Orleans, we join the Sunday Second Lines, the weekly parades that are organized by the different Social Aid & Pleasure clubs in different neighbourhoods. Brassbands, dancers, mobile bars, bbq’s on wheels, bikes, horses, cars, signs, sellers, they’re all rolling and all is self made/self organized. Someone tells us: ‘We don’t have much in Louisiana, but if we don’t have it, we make ourselves’. From our shallow outsider’s perspective the parade looks like a festive exotic Mardi Grass parade. But the more often we are joining in, the more it reveals its deeper value. The Second Line Parades seem to us not just an important celebration and continuation of cultural heritage but also an -almost hypnotizing- weekly relief from daily reality. Perhaps that also explains the absence of tourists?

Sunday Second Line, 17 March, 2018.

Activist/historian/artist mr. Ashton Ramsey in one of his themed suits, Tremé, March 2018.

Sunday Second Line, through the 9th Ward, 18 March 2018

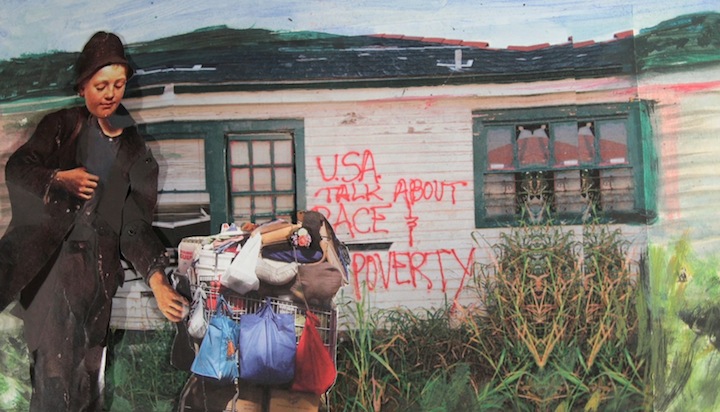

Hands on activism: Street signs- Take’m down Nola- New Orleans Murder map, March 2018

Besides the Sunday Second Lines we walk and bike every day through the neighbourhoods. Poverty, inequality and segregation are more openly visible than anywhere else we have been in the US. But also signs with protests, messages, warnings -placed in public space as an antidote- are very visible here. Every day we pass a profound sign on St.Bernard saying: ‘Think that You might be Wrong’. And another one reads: Always Film the Cops, as above, so below. And we bike along all the empty pedestals of the confederate statues -removed by the Take’m Down Nola Movement– as a pilgrimage to landmarks of change. We hope that it’s not just the removal of symbols, but the start of a real change. Later Maaike (Gouwenberg) shows us the St.Anna’s Episcopal Church, where pastor Terry keeps a record of all victims of violence in the city. On a huge white board in front of the church, he writes all their names with a permanent marker, mentioning their age and cause of death. It is an impressive and confronting monument.

We wonder if it is actually possible for us NOT to make a work of art here in Nola, but just to research. There are so many urgent topics that need to be addressed, and our natural medium to do so is art.

St.Bernard, March 2018

St.Claude, March 2018

Confederate statue removed by the Take’m Down Nola movement, 2018

Part of pastor Terry’s NOLA murder map, St.Anna’s Episcopal Church, 1313 Esplanade Avenue.

Meeting Pea (start of FREE BIRD RADIO)

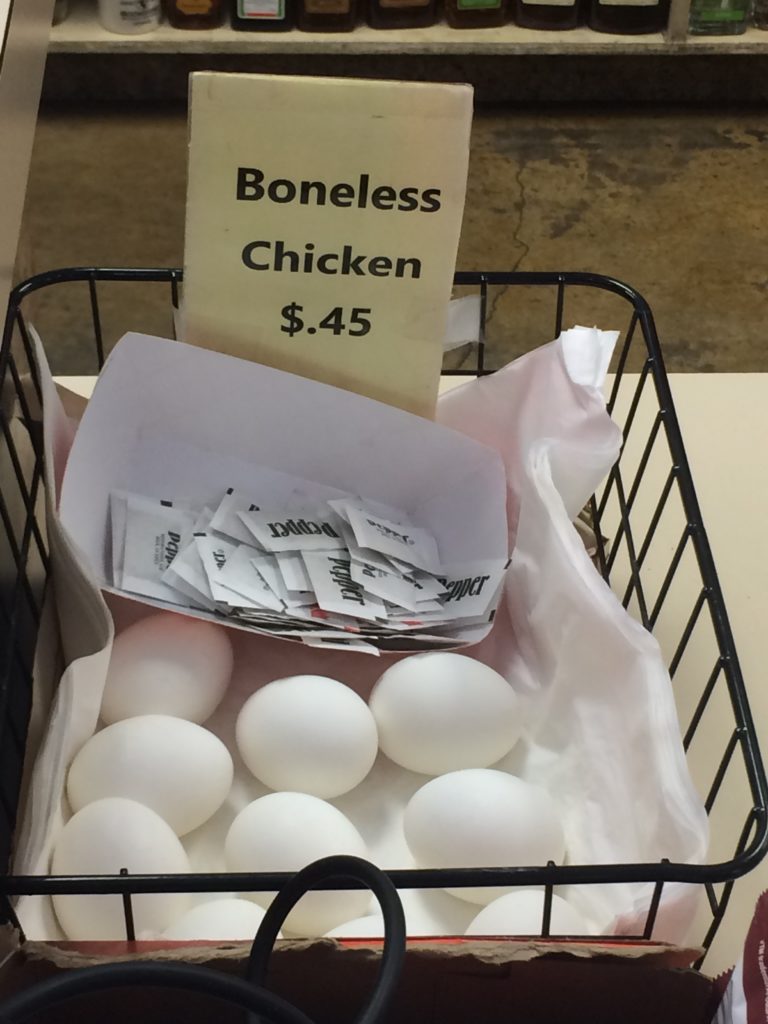

One day in March we meet Pea for the first time, the peacock who lives in our neighbourhood. Pea used to live in the zoo but was freed from his cage by hurricane Katrina. Originally there were three peacocks, but sadly enough one disappeared and one was -according to rumours-probably killed for his meat and feathers. Already for twelve years Pea lives in a tree on Paris Avenue. Mr. Benny, one of our neighbours, feeds him a daily breakfast of donuts and apples. He is the only one who is able to approach Pea. Mr. Benny thinks that although Pea is a free bird now, he isn’t always happy. Pea always has to watch his feathers as danger is around the corner for him and mr. Benny thinks he’s lonely, looking for a mate. For us, Pea became a (strange) symbol of freedom and he became -without knowing it himself- the starting point of a new work: FREE BIRD RADIO, a political radio show for birds. (later more about this work)

Mr.Pea in Bruxelles Street

Meeting Becca Begnaud in Lafayette

Via Deltaworkers, we get to know Cajun healer Becca Begnaud in Lafayette.

Becca treats her patients according to Cajun tradition, making use of prayers, her bright intuition and rituals from Native Americans. Last years there is an increasing interest in alternative ways of healing, perhaps because of an unaffordable or failing health care system or because one lost trust in the pharmaceutical industry. We hit it off immediately with Becca and we’re all interested in undertaking something together. Next to her house is her healer’s practice, based in a former Beauty Salon, that she wittily calls her Inner Beauty Salon. Becca invites us for a healing session with her clients, who approve our presence in the salon. We take part in a group meditation, a therapeutic drawing session and an emotional group talk. The clients- a mother and her two daughters- are not bothered at all by the presence of these two artists. Even more than that, they see it as a favorable sign. Like many people we meet, they have never been outside the US and find it interesting to meet two people from The Netherlands. The session is intimate, intense and we are grateful that we were part of it. In the evening Becca takes us to a workshop with the curious title How to die well in the local library, a workshop to address taboos around dying. She also takes us to Opelousas, according to her the most impoverished city of Louisiana, where we visit the statue of Amédé Ardoin and learn about his story. And she takes us to a befriended artist, who lives in a social housing project in Houma. A couple of weeks later we will return to Lafayette to conduct a meditation drawing workshop with Becca and other healers in the Inner Beauty Salon.

Memphis & Selma.

We visit the National Museum of Civil Rights in Memphis, to learn about the history of the civil rights movement. We spend almost six hours in the museum, definitely a personal museum record. The museum is based in the former Lorraine Motel where dr. Martin Luther King was shot in 1968. From a building across the street one can look through the window that was used by the assassin. From this window we can also see white bird’s nests hanging peacefully on a rope. They’re probably made by the residents of the building, as if someone wanted to chase away demons from this place.

After Memphis we visit the city of Selma, Alabama. Here we visit the Brown Chapel and the Edmund Pettus Bridge, iconic locations of protest and violence of the Civil Rights Movement. In the evening we start to watch the 14-part documentary Eyes on the Prize, and later we see Spike Lee’s documentary When the Levees Broke another time. There are definitely a lot of demons here that still need to be chased away. Way more then we thought before. It is a very humbling experience.

Memphis, Tenessee, view from the very window that was used by the assassin of dr. Martin Luther King in 1968. The birds’ nests in the work FREE BIRD RADIO are inspired by these.

Recording bird’s sounds for FREE BIRD RADIO on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, Selma, Alabama.

Community Bike Shop RUBARB

We hear about RUBARB (Rusted Up Beyond All Recognition Bike shop), the post-Katrina community bike workshop run by volunteers in the Upper Ninth Ward. After Katrina, they started collecting orphan bikes in the streets to fix and re-use these.

At Rubarb’s you can repair your own bike, or learn how to repair a bike. Kids are encouraged to ride bikes, learn to fix bikes and can get their own bike by earning ‘bike points’. And of course it is a friendly hang-out for anyone, a corner store. That things are not easy in this neighbourhood, we notice when we read a flyer that is casually posted on the wall: an offer for free bus services to various prison facilities, to visit your loved ones, complete with time schedule. We can’t even imagine seeing a flyer like this in a community center in The Netherlands.

At Rubarb they always need more volunteers, there are so many things to do. The walls on the outside need new murals and we volunteer for this task. The kids like drawing and painting so much and we make a drawing table.With them we will try to make a design for the mural. We buy materials and we visit RUBARB every Wednesday from now on. Good to be part of the RUBARB family.

George fixing bikes at RUBARB, Upper Ninth Ward.

Rubarb, post-Katrina bike workshop run by volunteers, Upper Ninth Ward.

27 March

On our search for local healers, Becca Begnaud takes us tot he Louisiana Himalaya Association, the smallest buddhist center of New orleans, where we can attend a Chöd practice (a ritual for ‘cutting’ through hindrances and obstacles such as ego, ignorance, anger).

We also visit the center’s annual Vision Fest, a gathering for alternative healers where we a.o. meet the Jin Shin Jyutsu healer Eric Pollard, who later gives us a class about Jin Shin Jyutsu in the local Healing Center.

Saskia Janssen, Tom Cox, Becca Begnaud, bij de Louisiana Himalaya Association, maart 2018.

In between all activities we make field recordings for a new work; a radio show for birds for the sound exhibition Lûd in a forest (the Rijsterbos in Friesland) in The Netherlands. Initially the plan was to create a musical radio show for birds, with music especially composed and played for birds by musicians from New Orleans. The idea was to connect two very different places in the world via music and via migratory birds. Probably many of the birds in the forest in The Netherlands frequent the Southern States where important breeding areas for migratory birds are.The idea was also to create an exercise of putting oneself in the position of ‘the other’, even if that other is a bird. Will birds like listening to human music in the same way as humans can enjoy bird sounds? And if they do, what would they like to listen to? Is it possible to compose music for birds?

However, during our stay in New Orleans, the concept of the work is gradually shifting. It becomes more political. It becomes a radio show for birds with an underlying message for humans. The subject becomes Freedom & Captivity, rather big subjects, but in the context of the history of New Orleans, the southern states, the police brutality and the Black Lives Matter movement it is an essential and, unfortunately, topical theme. And birds seem a good metaphor too, they’re often used by humans as symbols of peace or freedom, though also locked in cages by humans.

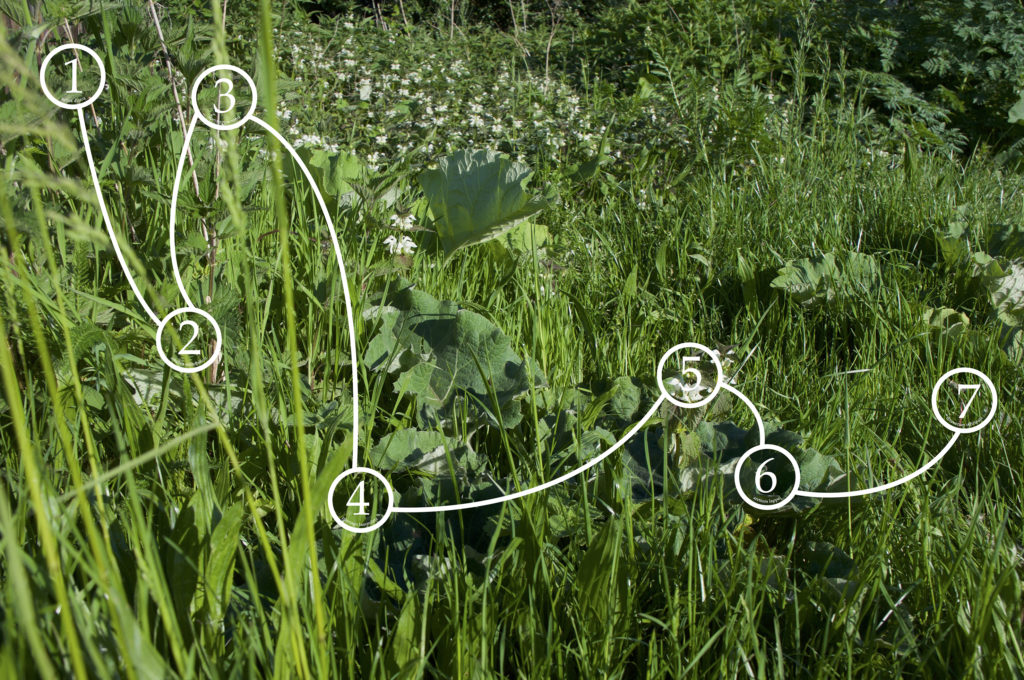

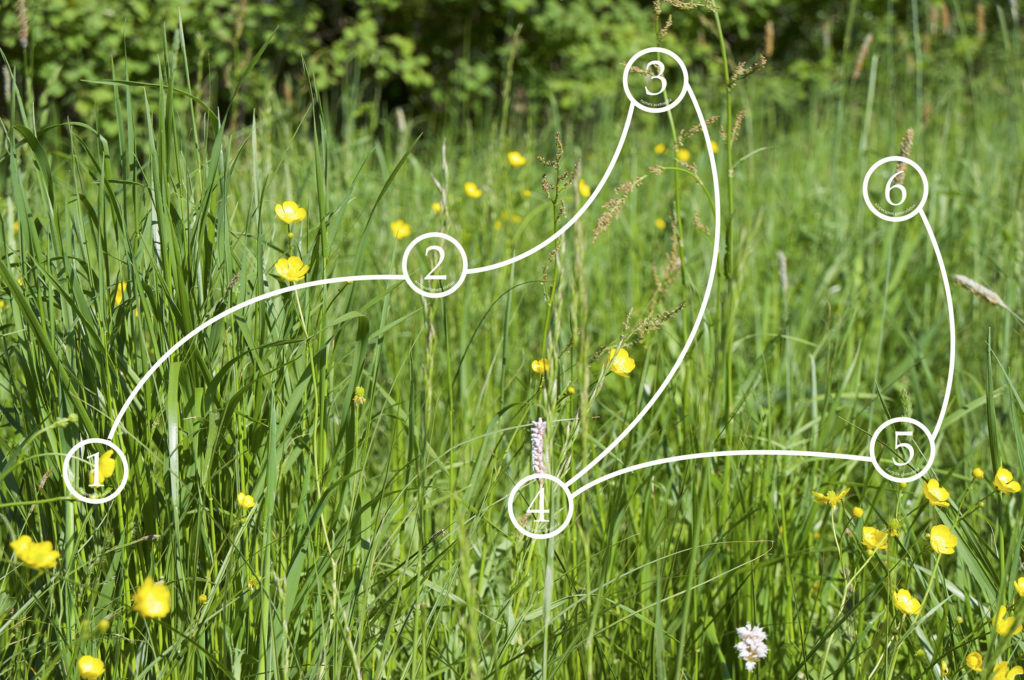

From now on we also make field recordings of birds on places of interest for birds ánd humans connected tot this subject and we start to collect material to make bird’s nests from, mainly protest flyers. Pea, the neighbourhood peacock that was freed from the zoo, seems a very symbolical starting point.

Mr. Pea, the free peacock, on the porch of mr. Eddy, Bruxelles st., April, 2018

Recording in Chicot State Park, bird sanctuary, April 2018

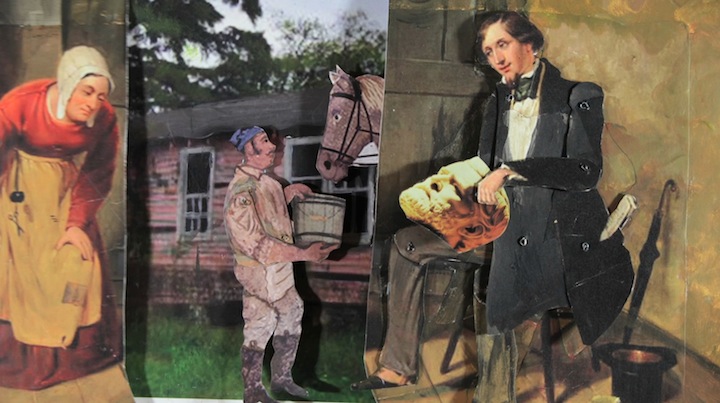

Making drawings at Becca’s Inner Beauty Salon

We are going to Lafayette for the mediation drawing workshop that we organise together with Becca Begnaud. Together with Becca’s guests we will copy classical, anonymous meditation drawings from the Tantric Hinduism tradition. There is not much known about these drawings, but what we do know is that these were used as tools to meditate and to train one’s mind, centuries ago in India. They were not considered as works of art, nor is there a traceable author or designer. The designs are passed on by generations of painters in a time there was no mechanical way of reproduction available and therefore the making of the drawings seems -in the perspective of art- an ego less practice.

At Becca’s we are not making individual drawings but we pass the paper and collectively work on each drawing. Calmly we produce a supply of drawings together, for each other. Meanwhile we talk about ego, authorship, motivation, intention and appropriation. Can we do this? Can we ‘use’ something from a culture that isn’t ours in order to meditate, to cure, or just to have a collective moment of reflection while painting these? Will all these positive things justify copying these drawings, if we don’t consider these as art works and do not exhibit these?

At the end of the afternoon we all pick a drawing and the other drawings will be given to patients of Becca or to whoever needs them by. One is for the Inner Beauty Salon and will be hanging in between other power objects. Becca’s thinks it is not a coincidence that this ancient drawing travelled all the way through distance and time to her practice. Her intention is to incorporate this way of meditation in her own healer’s practice. Drawing was already a vital part of it; it is very direct, meditative and if it fails, so what, throw it away! And actually, by working collectively on drawings, there is no failing, the drawing becomes merely a cherished memory of a collective moment.

Drawing meditation at Becca Begnaud’s Inner Beauty Salon, April, 2018

Drawing meditation at Becca Begnaud’s Inner Beauty Salon, April, 2018

Saskia, Bonny, Becca, in Becca’s kitchen, Lafayette, April 2018

Collaboration

The longer we are in Louisiana, the more we understand why Deltaworkers is a research residency and the more we appreciate that. It is so different from the other cities in the US where we have been.

There seems to be more segregation, more inequality, or at least this is more visible, on the surface.

For years already we love working together with locals, with ‘non artists’. Here that is not a natural thing to do specially when the (foreign) artist is white and the local is black. Here in New Orleans we feel more white privileged artists than ever before. Basic questions are: who wants what from who, and who will benefit from it in the end? What is the artist’s underlying motivation? And is the ‘collaboration partner’ not just part of the artist’s agenda? Fair questions and even after our long term experience with the Rainbow Soulclub, it is very essential for us to rethink these questions. When we attend lectures and artist talks in New Orleans, the audience seems always alert and keen to ask critical, confronting questions as many subjects are seen -and taken for granted- only from a white perspective.

Our (white) fellow resident Io Cooman, photographer from Belgium, would like to make portraits at the (black) Social Aid & Pleasure Clubs but despite her efforts she doesn’t manage to get access tot he clubs, partly because people are hesitant to help her and try to convince her that this is not a good idea at all for a white photographer. “Who will benefit from this at the end?” is the rhetorical question. Of course that is a more than fair question especially here in the context of Louisiana, with the long history of inequality and exploitation of the African Americans. But the thing that bothers Io the most is that she can not ask the people herself, whether they would be photographed or not. The fact that other (white) people think for them, and decide that ‘they will not like it’, without even asking them also doesn’t feel right. Isn’t that called white paternalism?

At the end, Io doesn’t succeed to make portraits at the Social Aid & Pleasure Clubs. But because she spends so much time in the streets, meets so many people ánd because she is sincerely interested, she finally finds interested people. At the Sojourner Truth Community Center she is allowed to install a make shift photo studio. The elderly ladies who frequent the center are in for it; it’s entertainment for them and also a chance to get free and professional portraits. Saskia joins Io to assist. No one in the center is bothered by the photo studio or by Io, it’s the opposite. The ladies are truly surprised by the professional and cheerful quality of the photos and some of them request a second shooting, in a different outfit, or to improve their way of posing.

Assisting fellow resident and photographer Io Cooman with making portraits at the Sojourner Truth Center. (photos by Io Cooman)

Newcomb Art Department of Tulane University

On 17 April we give a collective talk together with Maaike Gouwenberg for the students of Tulane University on a.o. collaboration, Deltaworkers and Rainbow Soulclub. Two days later we visit the MA students in their studios for individual talks about their works. It’s a small but very engaged group of students. We invite some of them to join our next meditation drawing workshop.

R.U.B.A.R.B.

In the meantime we continue our weekly activities at Rubarb. We brainstorm about the mural and we organise a spray-paint-your-bike workshop because that’s by far what the kids like to do the most. We also join the annual Jazz Fest field trip, as the festival gives out free tickets to the Rubarb kids and volunteers and for every kid one chaperon is needed.

With R.U.B.A.R.B.’s Courtney en Byron at the Jazz Fest, visiting Black Indian Ronald Lewis of the House of Dance and Feathers.

Courtney en Chris, after the spray can workshop at R.U.B.A.R.B. Favourite colors: gold and silver.

On 24 April we are invited for Janneke’s radio show Outspoken at the local radio station WHIV, the radio station dedicated to human rights and social justice. During one hour we speak about local politics and gentrification in New Orleans and in Amsterdam and about Rainbow Soulclub, our inevitable subject when it comes to politics.

5 May, meditation drawings at Camp Abundance.

We conduct a second meditation drawing session. This time it takes place in the garden of Camp Abundance with the students of Tulane University, Becca Begnaud and newly arrived Deltaworkers resident Alexandra Martens. In a calm and concentrated manner we produce the drawings while the neighbours across the street are cutting and braiding hair at their porch, meanwhile looking at our activities with interest. We talk about inviting them over to join in but somehow none of us does dare to do so, thinking that they might be suspicious about our plans, or just simply think we’re crazy. (Saskia: I still wonder why I didn’t invite the neighbours that day, usually I’m quick and spontaneous to invite people to join in. Am I discouraged by the segregation situation here and therefor I am suspicious of other people being suspicious about me?)

May- Mexican border- Terlingua

We decide to go for another road trip, to feel more of the Southern vibes. We will drive through Texas, along the Mexican border to off-the-grid Terlingua and to Marfa where we will visit the Judd and Chinati Foundation and via San Antonio we will drive back to New Orleans.

Along the Mexican border at the Rio Grande, we find the social routes in the corn fields that are used by migrants. Here we record bird sounds for the FREE BIRD RADIO.

We learn about the various organisations called Border Angels who set out bottles of drinking water in the desert for exhausted migrants. Unfortunately there are other organisations who are searching for bottles in order to take them away. We also learn that there are many people living off-the-grid in a self sustainable way in the Texas deserts. Some of them have no desire to be part of current society and decided to turn their back to it. Others think that this is even worse, and they try to take all action they can to help migrants and fight racism.

The Rio Grande is much smaller than we thought, at some points only a couple of meters wide and very shallow. It is easy to cross by foot. We see many border patrol cars driving around in search of suspicious situations. We are very aware of being here on this location as again -privileged- artists and not as migrants. Recording birds seems not very important here and now, but hopefully the meaning will emerge later from the finished work. And doing nothing because it all seems useless is not our attitude.

Rio Grande, Texas, Mexican border, recording birds for FREE BIRD RADIO.

visiting Gary-off the grid- in Terlingua, Texas

Protest sign at the Mexican border, Terlingua, May 2018

Border Angels water droppings, Texas. (anonymous internet photo) (The water bottle will be of inspiration for a-message-in-a-bottle, later in May.)

George recording bird sounds on migrant routes, Mexican border, May 2018

Back in New Orleans

We continue recording for the bird radio, meanwhile entitled FREE BIRD RADIO. Via Maaike we’re in contact with local musicianTom McDermott. We record at his place: loosely he improvises four pieces especially for birds. One of them played in the ‘butterfly’ spirt of the late James Booker, one of his favourite New Orleans piano players. (described by Dr.John as ‘the best black, gay, one-eyed junkie piano genius New Orleans has ever produced’.)

In Royal street we find more musicians who are interested in making music for birds. It seems that musicians have a natural appreciation for birds and their songs. Musicians Anton, Jonny, Max, Perikles and Blandine will come a couple of times to Camp Abundance for recordings.

May 15, recording with Tom McDermott. (who has a paper bird hanging above his piano)

With musicians Perikles Dazy, Blandine Laroche and Anton Kerkhof at Camp Abundance, 15 May 2018.

19 May- Studio visit with mr. Ashton Ramsey

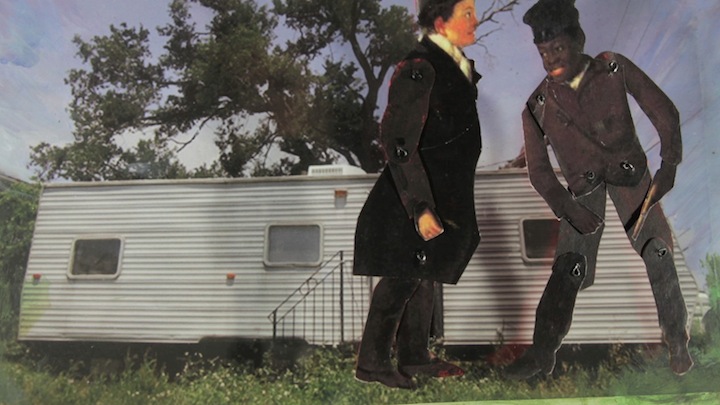

We are visiting mr. Ashton Ramsey, who we have met already in march during a Second Line, and who invited us over to his studio. Mr. Ramsey calls himself a historian/storyteller/activist/folk artist.

Already for years he is making paper suits. Every suit has another theme that usually is related to the current events. Previous themes include: Katrina, Black & White, Survival food, Earrings, Food coupons, Money etc. Originally mr.Ramsey wanted to become a Black Indian, like his brother who was making a new suit every year. But because he couldn’t afford the materials, the beads, the feathers, he decided to make low cost collage suits, decorated with meaningful newspaper clippings. Every suit has a matching paper hat and a pair of glasses spelling the title of the suit backwards.

His studio is in a small cabin in the backyard of his house in the Bywater.

Some of the paper costumes are in the Backstreet Cultural Museum, but unfortunately most of his costumes and his large newspaper clippings archive are stored here, in the humid climate. After years of making these incredible suits there is still no museum who is able to/or has the desire to conserve the suits. (for us hard to understand!) Because of negative experiences with journalists, mr. Ramsey doesn’t like to be interviewed anymore. Too many times people took advantage of him and his work.

But he likes to have visitors over and enjoys talking about his work. He has a mission too: he aims to keep the youngest generation off the streets and out of trouble, away from all criminal activities.

He still conducts workshops at schools and if his health allows him, he rides his bike in the parades, dressed in one of his suits, talking to everyone. Mr. Ramsey also talks about the neighbourhood, the gentrification. How it used to be a black neighbourhood with a lot of kids, who always came by. But these days the neighbourhood is completely white. Mrs. Ramsey mentions: ‘We really miss the kids, there are almost no kids anymore, all white couples now, but it’s good because they all like us and we like them all.’

Mr. Ashton Ramsey in his studio in the Bywater.

We also visit the Tremé Petit Jazz Museum several times. An initiative of jazz historian mr.Alvin Jackson who founded the museum in his home in Tremé because he was not satisfied with the mainstream museums. According to him these museums are not telling the true history of jazz, but are more of a tourist attraction. Mr. Jackson is a member of the Social Aid and Pleasure Club called The Black Men of Labour (‘because we work for our money, we don’t sell drugs’) In the museum every visitor gets a personal tour along the timeline on the wall while learning how jazz originated from different cultures all around the world. All the displays are self made, with love. Like mr. Ramsey and like the Backstreet Cultural Museum, mr. Jackson still can’t count on support of the city government, though all of them are obviously valuable for local cultural heritage.

In order to keep his museum open, mr. Jackson rents a room above the museum to tourists. While we visit his museum, a ‘Tremé tour group’ with a guide passes by. We’re surprised they don’t make a stop at the museum at all. Mr. Jackson explains to us that the big tour organisations from the French Quarter are not willing to share their proceedings with him, they rather simply skip the museum.

Back at RUBARB – mid May

On a Wednesday afternoon we arrive at RUBARB with boxes full of materials for a.o. the mural, but RUBARB is closed. More than closed, the doors and windows are boarded up with wood and there is a note on the door saying that the shop is ‘closed due to ungrateful and irresponsible behaviour of some’. We call the other volunteers and learn there have been violent incidents and it seemed to dangerous to keep the shop open. The rest of the afternoon we spend in font of the closed door, chatting with other people who came to repair their bikes. A week later there is also an incident in our own street, a drive-by shooting that kills a 20-year old man, one and a half block away from Camp abundance. Reality is approaching during these three months.

https://www.nola.com/crime/index.ssf/2018/05/homicide_bruxelles_street_new.html

Rubarb with boarded up windows, 17 May 2018.

Talk with Dawn DeDeaux at Camp Abundance

On 22 May we give a public artist talk together with Dawn DeDeaux, visual artist and founder of Camp Abundance. We feel kinship with Dawn and we have interest in similar subjects in our works. Together we decide on the title No Walls/ Flowers from the Cardboard Hotel. We will mainly speak about Rainbow Soulclub and Dawn will speak about the works she made in collaboration with young adults in a prison facility.

The Rainbow Soulclub, an initiative of Saskia Janssen and George Korsmit, involves collaborative projects between artists, art students and clients of The Rainbow Foundation, which provides shelter and care for homeless people and for long term drug addicts in Amsterdam.

Dawn DeDeaux has implemented experimental art programming for a 6000-inmate prison facility including projects for for juvenile offenders, which led to a long-term collaboration with the Hardy boys, two of New Orleans’ most notorious gang leaders of the late 80s through the early 90s.

Janssen, Korsmit and DeDeaux will show the work that was made during these partnerships and go into a conversation about their experiences they’ve shared with their collaborators.

Artist talk at Camp Abundance, Saskia, George, Dawn.

Artist and founder of Camp Abundance Dawn DeDeaux showing the Book of Judgements, May 2018

Dawn DeDeaux’ Book of Judgements.

No Walls/ Flowers from the Cardboard Hotelmade, artist talk at Camp Abundance (poster made by Erik Kiesewetter)

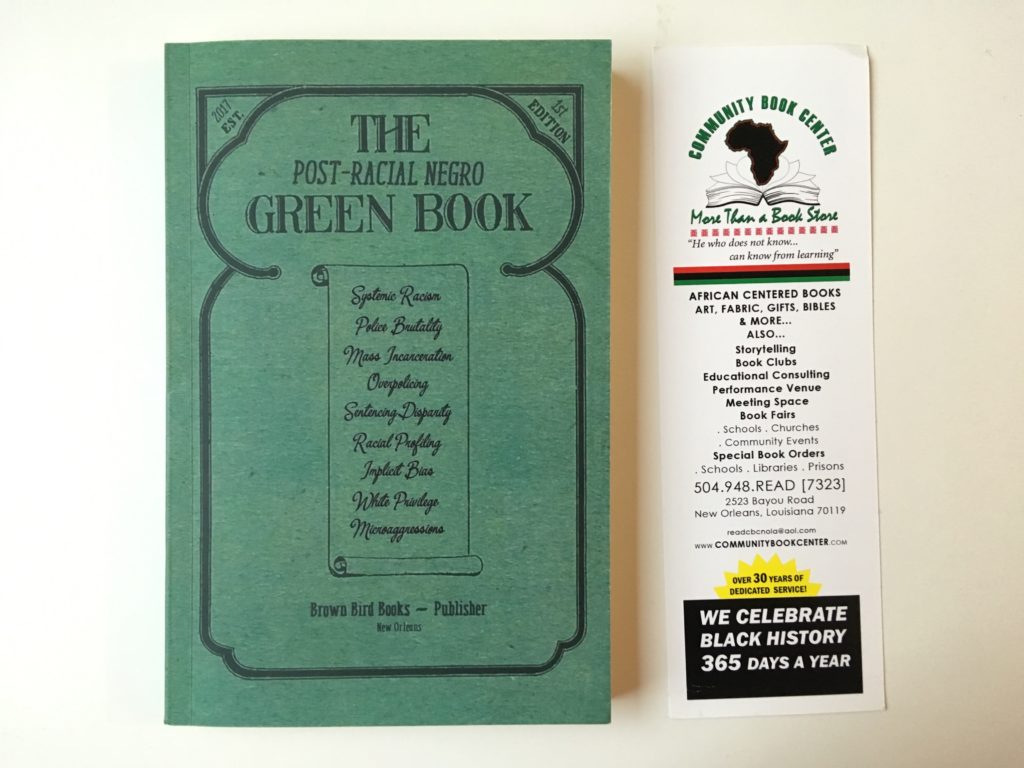

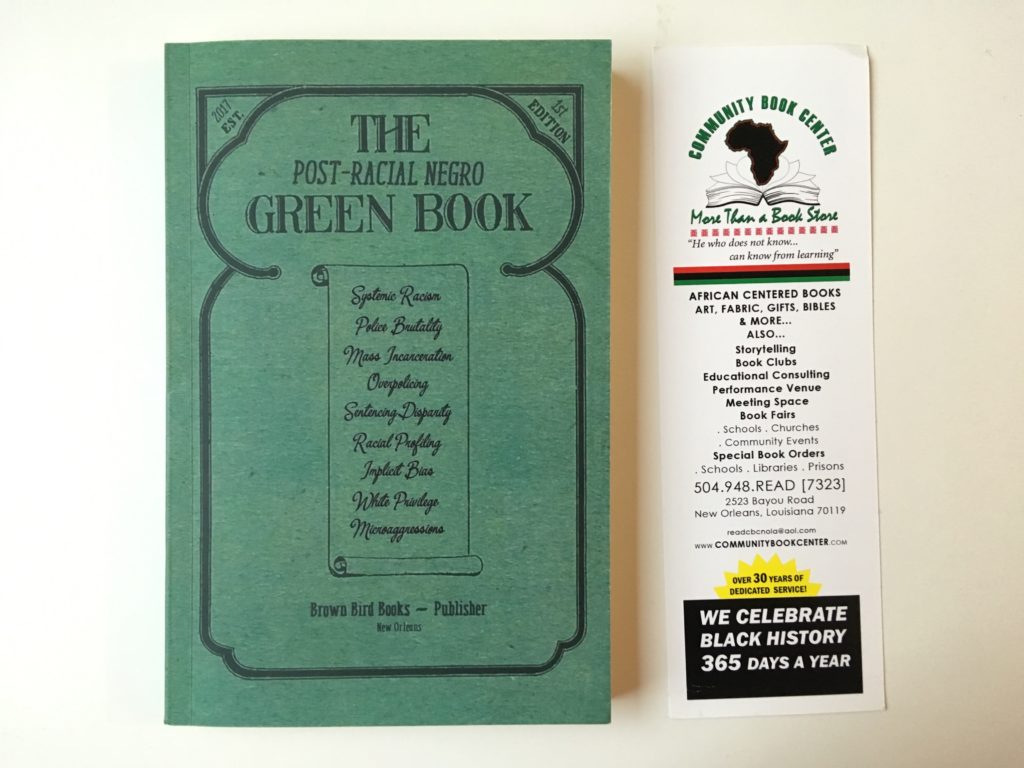

The Post-Racial Negro Green Book

In the Community Book Center we find the Post-Racial Negro Green Book, published by Brown Birds Books. It is a book that holds a collection of occurrences, information, and data that document a pattern of racial bias against black people in the 21st century. There is no commentary included in the book, just factual information. The format of the book, however, is commentary: it is based on the 20th-century Negro Motorist Green Book, which was published from 1936 to 1966. This segregation-era guide helped black travellers find safe harbors and services in a United States that did not welcome them as equal citizens. To us, outsiders to the US, the book reads like a horrifying history book.

The introduction of the book reads:

A traveler happened upon a small bird lying on its back in the road, its tiny claws pointing skyward. “Little sparrwow,” said the traveler, “what are you doing?”

“I have heard that the sky is going to fall,” replied the bird.

“And you expect that your spindly legs will prevent this?”

The little brown bird was silent for a moment, and then it answered:

“one does what one can”

To New Orleans

During the last week of our stay we decide to a give -symbolically- a piece to the city. New Orleans gave us so much during the three months. This city and her residents have showed us so much and made us think about many topics. We decide to send a message in a bottle to whoever stranger will find it, in the same spirit as the bottles left at the Mexican border by the Border Angels. We put a meditation drawing, a personal letter and a 20 dollar bill-for-a-drink in an empty water bottle. We attach the bottle to two jumbo balloons and head to Tremé. At first it’s not easy to find a spot, as wires and trees are everywhere in the way, but once released the balloons go up quickly and until they disappear as tiny black dots at the horizon, while some neighbors are watching.

Message in a bottle, to New Orleans, May, 2018

To New Orleans. Letter, drawing and 20 dollar note in plastic water bottle, May 2018.

FREE BIRD RADIO

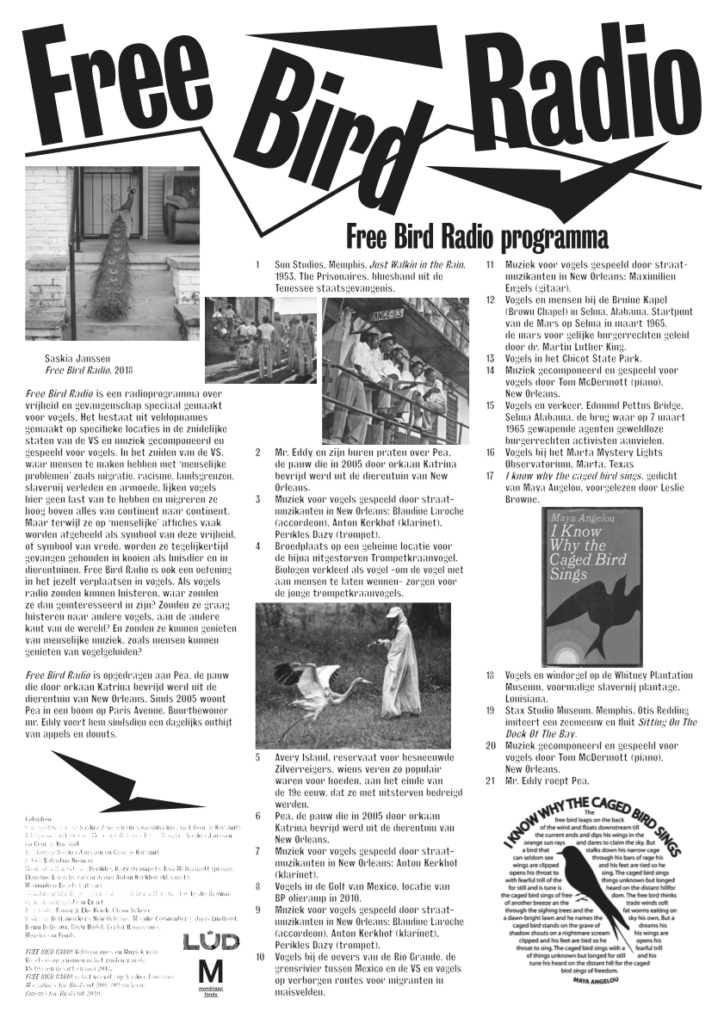

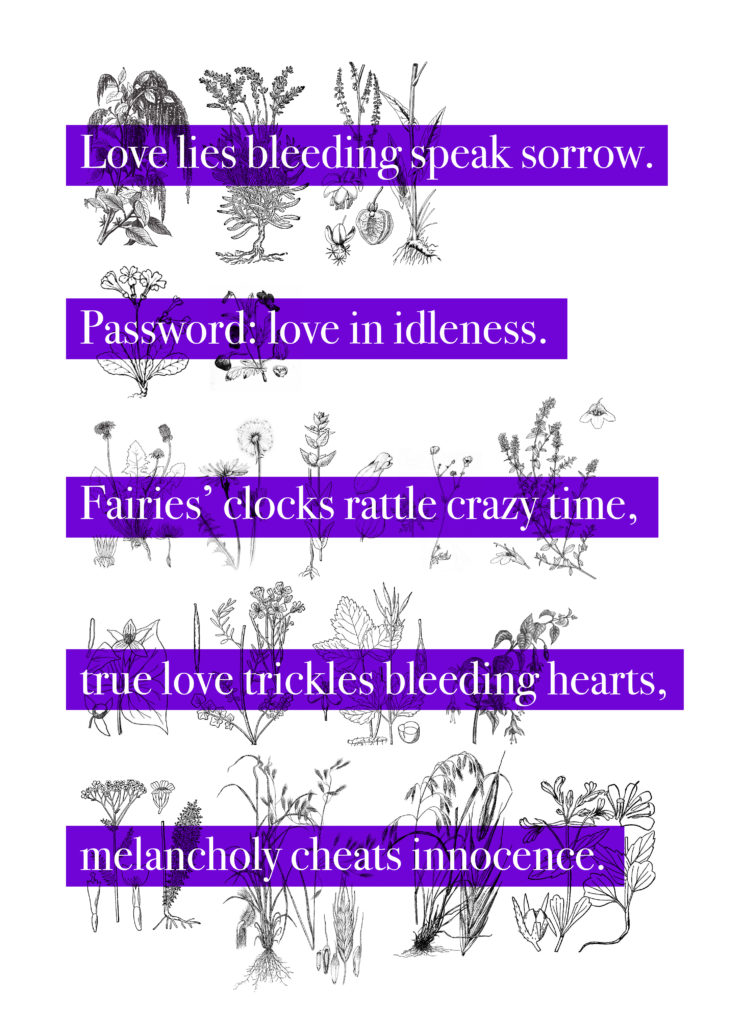

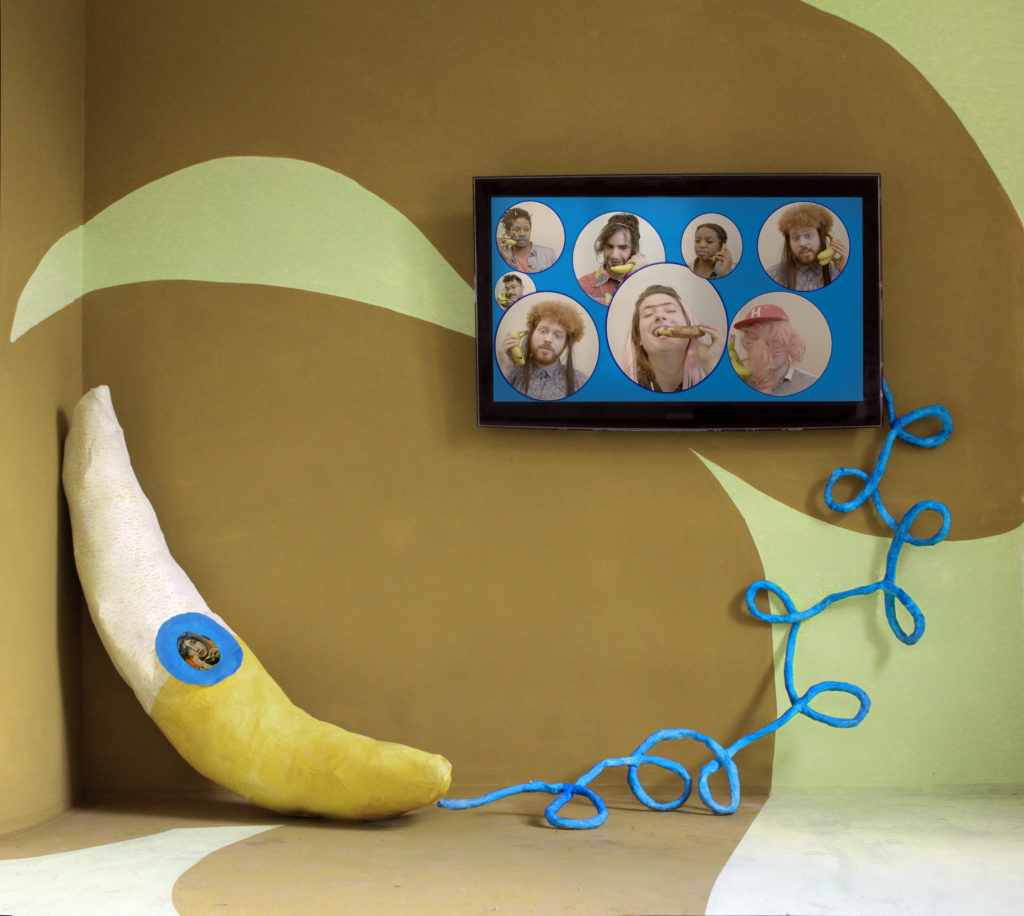

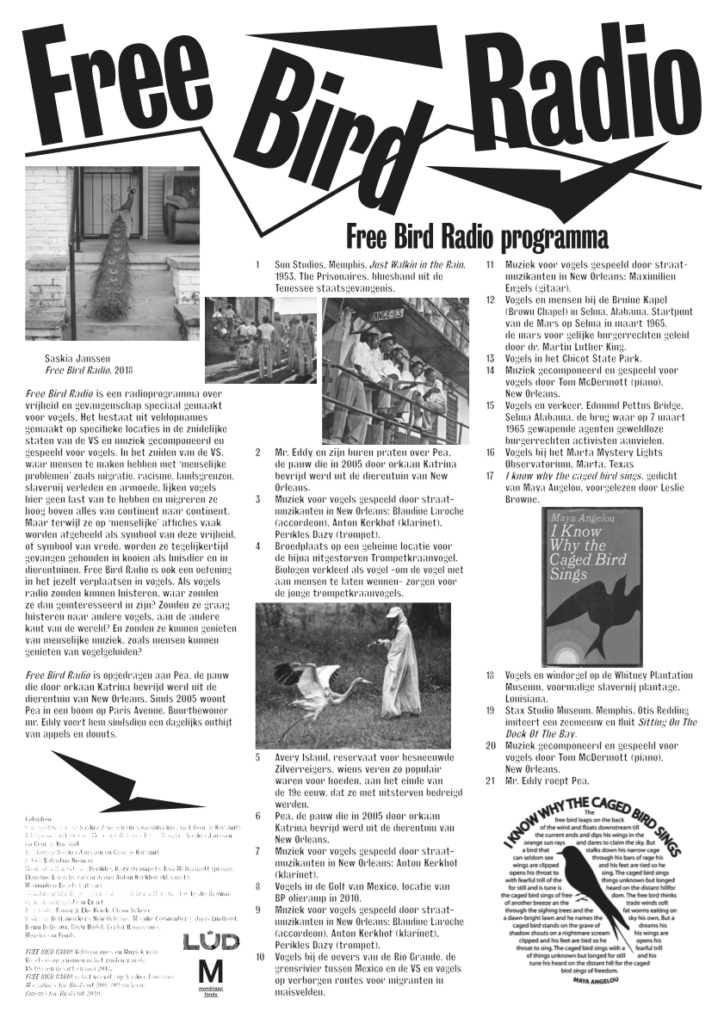

For the exhibition LÛD we made a installation/sound piece in a tree in the Rijsterbos, (a forest in Friesland, The Netherlands) and a riso-printed pamphlet. The installation consists of fourteen birdhouses made of gourds and protest posters. Above the birdhouses is a speaker attached with the radio show for birds called: FREE BIRD RADIO.

Saskia Janssen, FREE BIRD RADIO, 2018

Free Bird Radio is a radio show on freedom and captivity, especially made for birds. It consists of field recordings made on specific locations in the Southern States of the US, and music especially composed and played for birds. In the South of the US, where people have to deal with ‘human problems’ such as migration, racism, borders, the slavery past, incarceration and poverty, birds seem to be free from this while migrating high above all from continent to continent. However while their images are being used by humans as symbols of peace and freedom, birds are still locked up in cages and in zoo’s by humans. Free Bird Radio is also an exercise to put one self in the position of the other, even though the other is a bird. If birds could listen tot he radio, what would they be interested in? Would they like to listen to other birds, at the other side of the world? En could they enjoy human music, like humans enjoy bird sounds?

Free Bird Radio is dedicated Pea, the peacock who was freed by hurricane Katrina from the New Orleans zoo. Since 2005 Pea lives in a tree on Paris Avenue. Free Bird radio is also dedicated to Mr.Eddy, the neighbour who ever since feeds him a daily breakfast of apples and donuts.

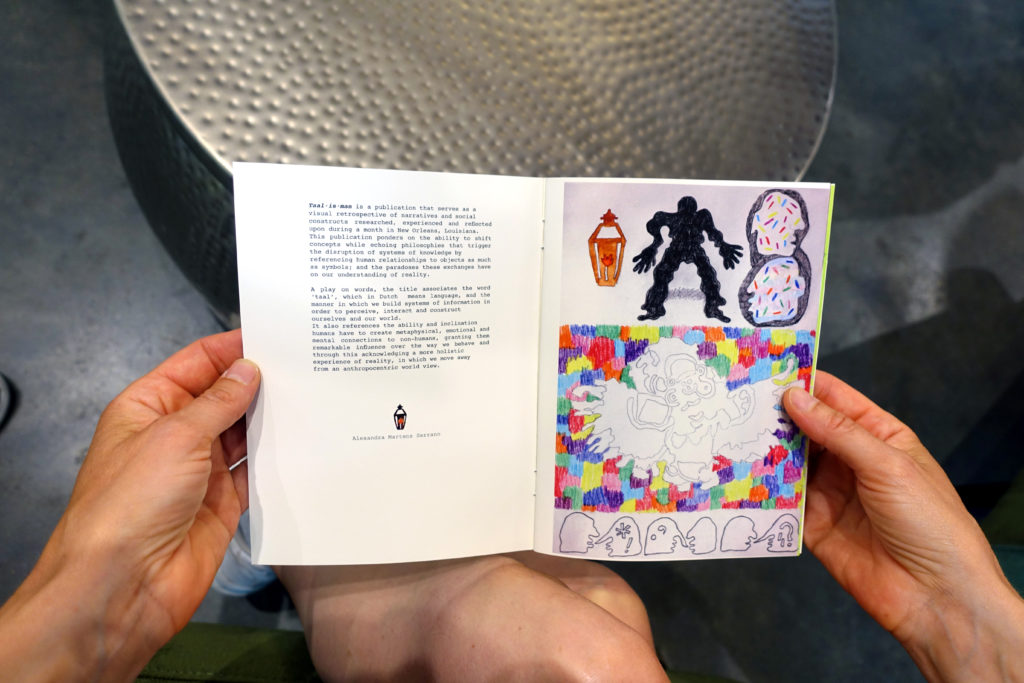

Riso printed program pamphlet of Free Bird Radio

Installing FREE BIRD RADIO, Rijsterbos, 4 Augustus 2018

We would like to thank Maaike Gouwenberg and Joris Lindhout for founding Deltaworkers in this incredible city and for taking care of our amazing stay at Camp Abundance. We would like to thank Dawn DeDeaux for founding Camp Abundance and for being the best host in the world. And A BIG thanks tot the Mondriaan Foundation for generously supporting our residency at Deltaworkers.

Saskia Janssen and George Korsmit, 24 October 2018.

Riso printed pamphlet for FREE BIRD RADIO