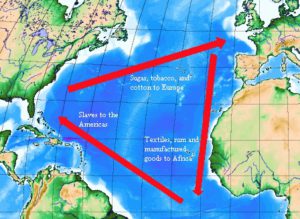

While looking for things to do in Mobile, Alabama, on itself an important place in the history of both the Civil War and the Civil Rights movement, and considered the birthplace of Mardi Gras, I stumble upon the remarkable story of Africatown. In 1860, the last ship with enslaved people strands in the harbor of Mobile. A successful bet proved that more than 50 years after the abolition of international slave trade (1808), it was possible to purchase and hide 110 enslaved Africans in a specially build (schooner) boat named Clotilda, and bring them to the US. Once on land the last slaves of African descend were split up for the course of the Civil War that broke loose almost immediately after their arrival (1860-1865). 60 people were kept on a piece of land owned by Timothy Meaher, who had arranged the illegal expedition. Once they were freed at the end of the Civil War they first tried to get back to Africa. When it became clear that that was not an option they purchased the land on which they were living from their former slaveholder and decided to build the next best thing: Africatown, the first self-governed city by people of African descend. When the other people who arrived on Clotilda heard about Africatown they all came down and managed for a long time to hold on to their way of living, including language, medicine, law and traditions.

While talking with people in New Orleans where I am doing a residency, it seems nobody has heard of the place, so I decide to go and visit Africatown to see this remarkable place with my own eyes. In the History Museum of Mobile, I get a map of the African American Heritage Trail, highlighting locations and persons who played an important role in African American history. The map includes Africatown, just a few miles out of Mobile, in the middle of an industrial zone. I start with the Welcome Center. What I find is beyond any possible expectation or even imagination. The sign indicating the presence of the Welcome Center is so old and made in such a home made style that the curled up letters nearly fall off. Of the Welcome Center itself only the brick stairs and the metal handrails leading to the door, are still standing. The rest of the building is turned into a pile of rubble. After visiting the Historic Mobile Preservation Society in the Minnie Mitchell Archives Building, I learn that the building was hit hard by hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the following neglect caused it to collapse entirely. Next to the visitor centre a monument was erected in 2007 by two African filmmakers Thomas Azinsou Akodjinou from Benin and Felix Yao Amenyo Eklu from Togo, who placed two busts in honour of Cudjo Lewis, the last slave of African descend and the last survivor of the Clotilda who passed away in 1935, and one of late Prichard Mayor John H. Smith, who took an major role in the establishment of the Africatown Folk Festival.

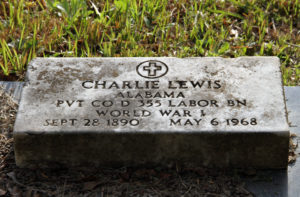

Both busts were decapitated in the middle of the night in 2012 leaving a very grim monument representing horror rather than honour. This horrible start of my visit is however only the beginning of what I can only describe as a blunt attempt to erase this unique place from history. The graveyard in front of the ruins of the Welcome Center, which includes most of the remains of the original enslaved people arriving on the Clotilda and their direct descendants, is slowly sinking in the ground and being taken over by nature. Graves are disappearing in the ground, some only leaving a cavity in the hillside.

Where are the surviving family members? Why is the city not taking care of its former inhabitants? Some graves contain soldiers who served in World War I an II and many other wars the US was engaged in since. Why do they get a different treatment after serving their country? Is the amended LD 1662, “An Act to Clarify the Laws Governing the Maintenance of Veterans’ Graves,” signed by Governor Paul LePage on the 6th of April 2014 and made law on the 1st of August 2014 not applicable to them? The site looks like a bombed hill, full of craters, where the dead would be turning in their graves if only they could find the space.

According to LD 1662, municipalities must ensure that grass is “suitably cut and trimmed,” “keep a flat grave marker free of grass and debris,” and “keep the burial place free of fallen trees, branches, vines and weeds.” As defined in law, it should also be considered and treated as an ancient burying ground, as it is a private cemetery established prior to 1880. What a shame!

The fact that the whole graveyard is sinking in the ground and slowly disappearing is made even more visible by the presence of a new graveyard, just next to the old one, levelled nicely at least 6 foot higher up. The contrast is mind-boggling.

I decide to go for a walk into what is left of Africatown. Almost half of the houses are abandoned, caved in or burned to the ground. I can but wonder what happened here. As a tourist destination it could not be more eerie and shocking at the same time. Although people are friendly, it is clear that a white tourist walking in the streets is like seeing a man walk on the moon; a very rare event. Cars drive by slowly and people ask if I’m fine or what I’m doing there. Another survey perhaps to shift taxes or resources around without making any difference on site? ‘An artist from Brussels?’, a woman asks surprised after she pulled over for the second time, ‘you make sure you leave town before dark, ok?’ When I ask her if I should be afraid of the people living there she sais: ‘oh no, it is the people from out of town who come here at night to cause trouble and make it unsafe’.

Why isn’t Africatown part of National Heritage? Or even International Heritage? A UNESCO World Heritage Site perhaps? What am I missing? This should be an attraction or pilgrimage site like Santiago de Compostella, or Lourdes. It should be commemorated both by black and white Americans for it represents the ultimate American (self made!) dream of self-governance. It’s a story of pride and perseverance in the most difficult situation one can be in and it represents a pivotal moment in American history. In 1985, the Alabama legislature officially recognized Africatown as an historic area and made provisions for its establishment as a State park with the name Africatown USA. To please the opposing industrial companies surrounding historic Africatown, a compromise was made pushing Africatown State park 3 miles away from the historical site. It was also decided that there were no original structures left from the early settlers, forcing historic preservation authorities to deny its recognition as official historic district. What an incredible mistake or set-up.

Due to a political shift the plans were never put in motion. Now, in the beginning of 2016, Mobile launched the Africatown Neighbourhood Plan in order to redevelop the site entirely. It looks good on paper, again, but what about the reality?

The inhabitants of Africatown are still fighting against the surrounding industrial lobby. On the16th of March 2016 there was a public hearing, again, to protest against the Above Ground Oil Storage Tank Zoning Amendment. Or plainly put: against the extension of big oil storage tanks in their backyard. Why isn’t Mobile fighting with them, why is Alabama not stepping in, and why is the United States overseeing this unique historic treasure go down the drain by allowing Oil companies to build storage tanks between the town and the river? Fossil fuels are part of the past. There is no need to store more oil since the majority of the already extracted oil worldwide can’t and won’t be used because of irreversible climate change. In addition, last year a turning point took place, making alternative energy become cheaper that fossil fuel energy. Wind power is now the cheapest electricity to produce both in Germany, the U.K. and Australia, even without government subsidies. In California, Chile, Australia, Turkey, Israel, Germany, Japan, Italy, Spain and Greece, solar energy is cheaper than fossil fuel for residential power, as well as Mexico and China for industrial power. Or as Sheikh Ahmed-Zaki Yamani, the veteran Saudi oil minister, said already in 2000: “Thirty years from now there will be a huge amount of oil – and no buyers. Oil will be left in the ground. The Stone Age came to an end, not because we had a lack of stones, and the oil age will come to an end not because we have a lack of oil,”. The end of the Fossil Fuel Age is near; do not invest in a corpse!

Invest in the sun, and not oil, and let it shine on Africatown, a historic landmark that should be part of the future and that will generate more revenue on the long run than any industrial investment.

A volunteer at the Minnie Mitchell archives explains why he never goes to Africatown because it is so tense and he feels he is not supposed to be there. He is doing his yearly duty however to count the homeless people that live under and around the Cochrane–Africatown USA Bridge, that opened in 1991, cutting Africatown in half. I ask him how many there are and he replies: I don’t know, I just count them’.

‘Are you talking about a dozen, hundreds or thousands?’, I insist. ‘Rarther thousands’, he answers reluctantly, ‘for sure also including some the descendents of the original Clotilda arrivals’. I sure hope there is room for them as well after the planned gentrification of Africatown. I hereby pledge to come back as a tourist again in a few years to see if history is repeating itself.

Maarten Vanden Eynde, April 2016